EXTENDED! CO residents can apply FOR FREE through December 1st. Apply now!

Secure your scholarship offer in just 2-3 days through December 17! Get started.

No waiting. No guessing. Join us for Instant Decision Day on December 3. Register now.

EXTENDED! CO residents can apply FOR FREE through December 1st. Apply now!

Secure your scholarship offer in just 2-3 days through December 17! Get started.

No waiting. No guessing. Join us for Instant Decision Day on December 3. Register now.

By Francisco Rodríguez, Rice Family Professor of the Practice of International and Public Affairs

When a massive earthquake killed tens of thousands of people in Turkey and Syria in February, activists around the world scrambled to raise money for relief efforts through platforms such as GoFundMe. They immediately hit a roadblock: US sanctions. To comply with regulations, GoFundMe told users, it would not only block fundraising efforts mentioning Syria earthquake relief, but would suspend the accounts of those making requests.

Facing public outcry, the Biden administration issued a special, limited-time licence exempting Syria earthquake relief transactions, after which GoFundMe allowed the campaigns to go ahead. Yet while this carve-out may have eased some difficulties in bringing aid to victims, no such exceptions exist for other countries under US sanctions.

This article was published on May 4, 2023 in The Financial Times. To continue reading, please click here.

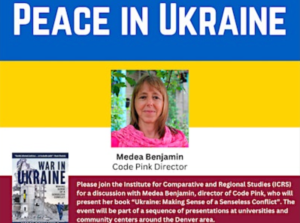

On April 4th, ICRS hosted peace activist and Code Pink founder Medea Benjamin. Listen here for a short conversation with ICRS Director, Aaron Schneider.

Utazi iyo ava ntamenya iyajya!

(If we don’t know where we came from,

we don’t know where we’re heading)

- Kinyarwanda proverb

The Africa Center and Students for Africa remember! “Kwibuka” which means “to Remember” in Kinyarwanda, begins on April 7th, and concludes July 4th on liberation day. The annual 100-day commemoration period is a global phenomenon that reminds us of our Ubuntu (humanity) and the horrors that could be fell us when we forget this requisite.

2023 marks twenty-nine years since the genocide against the Tutsi, moderate Hutu and Twa in Rwanda took place. Every April, the world and especially victims and survivors of the genocide join together to remember those lost and commemorate the atrocity that humanity had vowed never again! Kwibuka is a time for Rwandans and the global community to reflect on the past, and to continue to work on processes and measures to ensure that such an atrocity never happens again. For Rwandans, it is a time to reflect on the past and a future molded by collective trauma and reconciliation.

While tensions between Tutsis and Hutus were already high, the trigger for the genocide came on April 6th, 1994, when a plane carrying then Rwandan President Juvenal Habyarimana and his Burundian counterpart was shot down by unknown people. Upon his assassination, the Hutu extremist group Interahamwe, quickly organized, blaming the attack on “Tutsi Extremists” calling for total extermination of the Tutsi whom they branded traitors (from colonial experience) and dehumanized as “Tutsi cockroaches”. The Interahamwe hate speech was broadcasted through the radio across the country calling all Hutus to kill Tutsis and any sympathizers. In the ensuing 100-days an estimated 200,000 Hutu civilians participated in the killing of an estimated 800,000 people including Tutsi, moderate Hutus, and Twas; one-tenth of the country’s entire population at the time. Although the genocide took place over two decades ago, the impacts continue to linger, leaving no one untouched.

On April 7th, Rwandans across the country, diaspora, and the international community gather in Kigali’s Amahoro (“peace”) stadium to attend the annual commemoration ceremony. The ceremony is a time for Rwandans to unite in solidarity with one another, for a candlelight vigil in remembrance of the victims, and carry a torch as a symbol of commitment to ensure that what happened in 1994 never happens again.

Throughout the years, Kwibuka has become highly politicized, with those who do not attend the commemorations labeled perpetrators or family members of perpetrators. Many cases of arrest occur during the commemoration period due to subjective law. Outside of the three-month period of Kwibuka, the mention, discussion, and emphasis of ethnicity is in violation of the country’s “Ndi Umunyarwanda” (“I am Rwandan” law). The law was created to reinforce a post-genocide unified national identity. Yet, the most polarization of Kwibuka in the recent past was the renaming of the genocide in 2014 to restrict it to the killing of the Tutsis. This narrative has drawn criticism to the Kagame government’s handling of the commemoration period as well as the manipulation of the collective memory of the country. Critics argue and warn that there has been a sense of historical erasure of the many moderate Hutus and Twas who were also killed in the genocide, previously recognized as victims. Despite the controversy, Kwibuka remains a valuable time for Rwandans and the world to remember the victims of the genocide.

Rwanda’s resilience has stood the test of time, as the country remains at the forefront of African development and innovation. However, it is impossible to ignore the shared history and collective trauma that has pushed the country to where it is today. Rwanda is a solemn reminder of what happens when we as human beings lose our Ubuntu, and the 1994 genocide should always remain a reminder of the importance of human virtues, compassion, and unity.

This article was written by Dr. Abigail Kabandula and Natalie Impraim. Lindsey Mandolini served as editor.

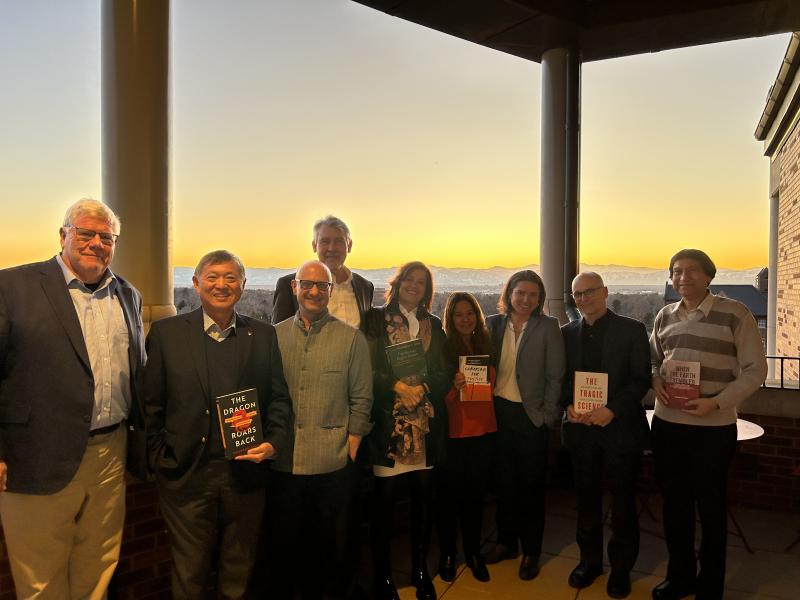

On February 7th, seven ICRS Affiliates celebrated their recent book launches at the Josef Korbel School of Global and Public Affairs, University of Denver.

Learn more about their work below!

George DeMartino

The Tragic Science: How Economists Cause

Harm (Even as They Aspire to Do Good)

Rebecca Galemba

Laboring for Justice: The Fight Against

Wage Theft in an American City

Micheline Ishay

Haider Khan

Rachel Sigman

Suisheng Zhao

The Dragon Roars Back: Transformational Leaders

and Dynamics of Chinese Foreign Policy

Aaron Schneider

China, Latin America, and the Global Economy:

Economic, Historical, and National Issue

How do you see your work fitting into a Korbel Institute for Comparative and Regional Studies (ICRS) with a focus on labor, democracy, and the global South?

As a political scientist, comparativist, and latinamericanist, my research and policy work is directly connected to issues of justice, security, rights, and equity in the “global south.” The Latin America Center directly engages with these issues and convenes events and speakers to stimulate dialogues. My personal research agenda also touches on many of these areas. I am currently implementing a field experiment with a colleague at UT-Austin and the help of several Korbel students to study whether ex-combatants from the armed conflict in Colombia experience hiring discrimination in their searches for formal employment, and how to remedy any such bias. My primary line of research focuses on how communities can protect themselves from armed conflict violence. That research, spanning several countries, emphasizes the empowerment of communities in the “global south” through supporting their local democratic institutions as the foundation of their advocacy and protection (they can also pursue their autonomous development with great security and protection of their rights). As part of ICRS’s COVID-19 and Democracy project, we also convened an expert working group to produce a report on how the pandemic affected democratic trends in Latin America. At ICRS, I also run the Korbel Asylum Project to involve students in helping asylum-seekers from the Global South improve their chances at winning asylum based on sound research.

How does your identity and positionality shape your work as director of the Latin America Center?

We all have our own unique identities and cannot change where we come from. But we can recognize our unique backgrounds as individuals and what they imply for our interactions with others—including for academic dialogue and research. We can leverage such awareness for more respectful and productive engagements. I recognize that I come from a particular background with particular characteristics, as I am visibly a White cis-male from the U.S. and come from northern California in the U.S. I also have many other invisible aspects—opportunities, experiences, and challenges that I had to overcome—that shape who I am. My awareness of my positionality helps me understand how others view me and how I can bridge any social distance to connect with people of different backgrounds, whether they are students, research participants, government officials, or colleagues and friends. In my case, because I work a lot with residents of rural communities and activists in Colombia and elsewhere, I regularly interact with people who come from quite different places than I do. I have written several reflections on how positionality enters into my research. I also discuss how positionality enters into my “partnered” policy engagement process with local peacebuilders. By recognizing our differences we arrived at an even more impactful presentation of our insights on atrocities prevention (also in our forthcoming book on Responsible Policy Engagement).

What advice would you have to students, activists, and policymakers in terms of building solidarity between North and South?

Sometimes building solidarity can be challenging, not only because of physical distance but also because of cultural distance and differences in lived experiences. But building solidarity is definitely possible, and it has perhaps been the most rewarding part of my research and policy work. It begins with showing up, and being reliable and consistent. It involves focusing on and valuing relationships, and approaching people with respect. Perhaps most centrally, solidarity involves not only making contributions and supporting others, but also valuing and representing the contributions of others. To do this, one must have an open mind and listen to all voices, from wherever they may come.

There is generalized unease with the Brazilian military, expressed by President Lula on the last 12th, which was generalized in the press and social media. This sentiment may be misplaced because, if the military failed in the January 8 crisis, the Republic has been failing the military for much longer.

When it comes to the military, all the presidents we've had since re-democratization failed because they played little role as commanders in chief. None of them made reform of the armed forces and the Ministry of Defense a priority, delegating or delaying and missing opportunities for greater presidential participation. The failure to reform effectively failed to comply with article 91, paragraph 1, item IV of the Constitution, which establishes that the National Defense Council is responsible for "studying, proposing and accompanying the development of initiatives necessary to guarantee national independence and the defense of the democratic State". This council never fulfilled its role, and the military are more consulted than subordinated to the priorities of the Presidency of the Republic. As a result, military activities are submitted to almost no external evaluation.

Worse, even with the history of military interventions in national politics, various governments have done nothing to reduce the political power of the military. On the contrary, they have become increasingly dependent on military agencies to build roads and bridges, distribute water, contain epidemics, fight organized crime and even guarantee elections, among other civil functions. As long as the military is central to public administration, it will have political involvement and bargaining power to remain insulated from civilian control.

Congress failed the military by never overseeing and intervening when the Executive failed to fulfill its role. Federal deputies and senators failed the military when they accepted a marginal role in the formulation of defense policy, and instead of developing qualified advisory oversight and public debate, submitted to the lobbying of formal and informal representatives of the military in the Legislature. Worse than that, Congress has always acquiesced, even when not necessary, to an exaggerated use of the military in civilian functions.

With the exception of Nelson Jobim, the Ministers of Defense failed the military by failing to amass qualified personnel, producing an unstructured hierarchy with limited effort to advance reform. None of them were able to develop a hierarchy adequate for analysis and management that could be independent of the military. Worse, they accepted that the military divvied up the Ministry of Defense by incorporating their fiefdoms and private agendas.

The Brazilian Judiciary failed the military when it did nothing to reverse the existence, a holdover from the military regime, of a parallel military judicial system with no equivalent in any democracy in the world.

Universities have failed to develop skilled defense expertise and knowledge and have never taken on a more central role in training the military. Most social scientists are averse, if not repulsed, to matters of defense and war in general.

The Brazilian military has failed itself. They never fully accepted being unreserved servants of the Nation and always flirted with the tutelage of democracy. They gave in to the temptation to expand subsidiary missions in exchange for an extraordinary budget, and accepted civilian positions in the Dilma, Temer and, mainly, Bolsonaro governments in exchange for financial gains, privileges and status that deformed and exposed their corporate interests.

Brazil's list of failures is long, and the general unease towards the military is unsurprising. What is surprising is how long it has taken to realize this fact.

Published originally in Portuguese here.

How do you see your work fitting into a Korbel Institute for Comparative and Regional Studies (ICRS) with a focus on labor, democracy, and the global South?

I often tell my students if they would like to specialize in any aspect of global politics to study Africa. Today Africa sits at the center of international power plays be it in security, development, climate change, or technological advancement. It promises to be economically and geopolitically important with a projected population of 2.5 billion people by 2050 and 3.1 in 2063, the largest free trade area with combined GDP of USD 3.4 trillion following the creation of the Continental Free Trade Area, and because of a significant concentration of minerals for global decarbonization efforts. Like most global south countries, Africa is not short of labor even though 90 percent of it is in the informal sector hence it is imperative for the Africa Center programming to emphasize labor. Suffice to say, Africa is germane in global politics and will remain so. Emerging powers China, Gulf States, Turkey, and now Russia are cognizant of the importance of Africa and have begun to position themselves to benefit by increasing their footprint through improved diplomatic relations, foreign direct investment, foreign aid, infrastructure development, and technology. The United States seems to have come to this realization albeit in efforts to counter China’s presence on the continent and has renewed its commitment at the second US-Africa Leaders’ Summit. It’s within this global configuration vis-à-vis Africa that my research unfolds. I focus on global governance and human security in the global south, particularly the drivers of conflict and fragility; terrorism, and prevention of violent extremism/countering violent extremism; multilateral responses to crises and regional organizations for peace and security and; emerging powers, relational power, and geopolitics.

How does your positionality shape your work as director of the Africa Center?

My positionality as a person of color, African, scholar, and woman originally from Zambia informs my analysis and engagement with global issues. As a Zambian woman, I learned quickly of the marginalization of Africans, the global south more broadly, and gendered identities in my work. I have been fortunate to participate in many policy advisory meetings, policy research, and to travel extensively across the world, in each of these spaces, I am conscious of who is missing at the table and why? I am also conscious of when and how I can highlight those voices and needs. Our programs and activities at the Africa Center aim to enhance the science-policy interface as well as integrate the voices of the community that we serve while highlighting marginalized voices; diaspora or continental.

What advice would you have to students, activists, and policymakers in terms of building solidarity between North and South?

One thing that has helped me when interacting with people from diverse backgrounds is having an open mind and thoughtfully listening as well as appreciating the context informing one’s standpoint before engaging in a discussion. Meaningful collaboration between the global south and north can truly happen in the context of openness and willingness to listen and learn new ways of thinking about issues. Particularly the global north ought to appreciate that the global south has something to contribute, their knowledge and experiences are valid and significant. On the part of the global south, empathy and tolerance are key knowing that “A sweet potato cannot be easily straightened” as the Bemba saying goes. It takes a lot to change the negative image and characterization of the global south in the Western mindset. However, with time and continued meaningful interactions, these perceptions shift fostering mutual respect and positive collaboration.

Singumbe Muyeba, PhD, Assistant Professor of African Studies, and Abigail Kabandula, PhD, Director of the Africa Center

The continued buzz from last month’s US-Africa Leaders’ Summit appears to challenge the long-established observation that the African region occupies the lowest priority in US foreign policy. In his own words, President Biden declared that his administration is “deadly earnest and serious about this endeavor”, meaning the US relationship with Africa. Indeed, the summit and its immediate aftermath have created an impression of prioritization of Africa in US foreign policy for the future, but there were many missed opportunities which indicate that this might be temporary.

The Summit was held in Washington DC from December 13 to 15, 2022. Only the second in eight years, the summit brought together 49 heads of state and government, the African Union, business leaders, journalists, civil society, youth, and the African diaspora communities. The aftermath has seen the appointment of Ambassador Johnnie Carson, a seasoned US diplomat, to oversee the implementation of the agreed-upon resolutions. Additionally, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen embarked on a 10-day visit of three African countries, coinciding with IMF Managing Director Kristalina Georgieva’s visit to Zambia. President Biden has promised to visit the continent along with a host of high-level officials, which would be the first time a US head of state would visit the continent since President Obama’s visit in 2015.

There are clear successes that have emerged for the US. The three-day undivided attention given to Africa by the most powerful nation on the planet demonstrated that the Biden Administration is indeed deadly serious about the relationship with Africa. Moreover, the efforts made since the administration came to power show remorse for the public disparagement and derision endured by Africa under the Trump administration. The Biden administration brokered 15 deals and made commitments worth $55 billion over the next three years. Part of the funds will ensure that the US economy will have access to Africa’s metals to aid its clean energy transition. On the democracy front, the US sent a clear and powerful message to the governments of Guinea, Mali, Sudan and Burkina Faso, which came to power through coups d’etats, that undemocratic rule isolates them from US and global politics. Eritrea and Western Sahara were also left out due to lack of diplomatic relations with the US. Underlying this exclusion is deterrence to leaders who might be contemplating remaining in power undemocratically. The special meeting on the second day with governments preparing for elections this year solidified this message. Finally, the Biden Administration managed to maintain African support for its strategy of militarization of US-Africa relations that has defined a major part of US-Africa relations since the George W. Bush administration.

Like the US, African governments had several significant successes. African leaders appreciated that the continent has been taken seriously beyond its relations with former colonial powers, albeit as a single African continent rather than individual countries. Nothing says we are deadly earnest and taking you seriously than billions in federal funds at a time when countries are in debt default, high debt distress, or in debt distress. Further, securing US support for the inclusion of the AU in the G20 and for a permanent seat at the UN Security Council was a remarkable success for African voices being welcomed in global governance. The summit also infused confidence in the AU’s Agenda 2063, which had outlived its 15 minutes of fame in the media. It is almost 10 years since Agenda 2063 was instituted and yet the US only mentioned it for the first time in 2022. Unintendedly, a significant success for African governments is a return to the Cold War position of powers competing for the attention of African governments and having the option of using that to their strategic advantage.

Despite several successes, there are missed opportunities for the US. The summit failed to demonstrate long-term US commitment indicating that this prioritization might be once-off or short-lived. No date for the next summit was set. Neither was there expectation that there will be prioritization beyond the Biden Administration. Irregularity of timing of summits, as opposed to the predictability and regularity of the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation, Turkey-Africa Summit, Russia-Africa Economic Forum etc., leaves lingering questions regarding the US commitment and prioritization of Africa over the long term. Further, the US missed the opportunity to institutionalize the event under the Bureau of African Affairs. On the leadership front, despite committing $100 million over several years, the summit missed the opportunity to amplify the goals of the Obama Youth African Leaders Initiative (YALI) in the sense of reminding some of the presidents and recycled politicians that have overstayed in power that it is time to institutionalize succession plans, to let go, and hand over to the youth as a way to strengthen democracy. A case in point is 90-year-old Cameroonian president Paul Biya’s hot mic incident which revealed that he was unaware that he was at the summit while delegates and the world watched him embarrass himself, his country, and the continent. Further, the summit missed the opportunity to guarantee future democratic rule by grouping youth engagement with diaspora engagement. Youth engagement seemed to be an afterthought. Finally, the well-organized summit showed that much effort went into masking that the summit was a frantic attempt by the US to join the party as a latecomer. It was a clear attempt by the US to enter Africa as an arena of great power competition with China, Turkey, Russia and the Gulf States. Only time will tell if Africa was being prioritized over the long term or the US was attempting a second entry into the competition following the 2014 summit.

There were also missed opportunities for African governments. They did not secure a strong commitment from the US for a definitive end to the debt problem. What is more, they missed the opportunity to seek structural change to commodity pricing to address declining terms of trade, intellectual property rights, and fairer trade which is a critical path to sustained economic power, inclusion in international political decision making and long-term prioritization of the region. These demands have been on the table for Africa at least since the 1970s and in some cases since the independence struggle.

In sum, the summit and the continued buzz is emblematic of the prioritization of US foreign policy in Africa in the short-term, but the missed opportunities by both parties indicate that long-term prioritization in US foreign policy remains questionable. In addition to the post-summit follow-through by the US seen so far, institutionalization and regularization of the summit and structural changes in trade are needed to guarantee prioritization for the summit not to just end in a buzz.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to thank Prof. Aaron Schneider, Director of ICRS for the idea to write an opinion piece on the summit and for comments made on the initial draft.

How do you see your work fitting into a Korbel Institute for Comparative and Regional Studies (ICRS) with a focus on labor, democracy, and the global South?

In my research and teaching, I focus on comparative politics and area studies as I compare issues related to Democracy across different regions, especially the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region and East Asia. My work mainly investigates the political economy, the public policy-making process, and the security sector concerning the transition to Democracy in the global South, with some experiences driven from the North.

How does your positionality as scholar from Egypt with a PhD from a Japanese University shape your work as director of the Japan Program?

I grew up in a middle-class family in Cairo, Egypt. However, I was lucky enough to move to Japan at a young age to study for my master's and Ph.D. degrees at two different universities in Tokyo and Hokkaido (the northern main island of Japan). The transition from Egypt to Japan was an eye-opening experience to investigate and learn about the political economy of development and civil-military relations in East Asia. What I learned from this experience did help me to understand structural issues impeding democratization and sustaining authoritarianism in Egypt and the Middle East. As a director of the Japan Program, I build relations with NGOs, Media, Universities, and governmental institutions in the U.S., Japan, and the Middle East to better understand and shape the current transition in world politics.

What advice would you have to students, activists, and policymakers in terms of building solidarity between North and South?

One great faith I have in life is that miscommunication constitutes most of our daily communication and interaction as ordinary people. This miscommunication usually leads to our daily problems and stereotypes. It henceforth leads us to wrong decisions that may waste our time, resources, and efforts and downgrade the quality of life in our communities. This miscommunication is not only caused by speaking different languages or coming from different social and cultural backgrounds, but also it is caused by the need for more efforts to communicate, open sustainable dialogues, and assure each other. If I implement this in world politics, I claim that much of the problems we encounter at the global level as state and non-state actors can be attributed to this lack of communication, dialogue, and assurance between the North and the South. Therefore, I advise students, researchers, activists, and policymakers to establish dialogues to communicate and understand each other better. I will use the Japan Program as a platform for communication, understanding, and dialogue between the North and the South.

How do you see your work fitting into a Korbel Institute for Comparative and Regional Studies (ICRS) with a focus on labor, democracy, and the Global South?

From our inception, the Center for Middle East Studies has been focused on the themes of democracy and human rights. Thus, the new focus of ICRS on labor, democracy, and the Global South fits very nicely with our previous work. In many ways, it is perfectly consistent with what we have been doing for the last 10 years. We hope to continue to pursue research and advance programming that amplifies the themes of human rights, social movements, and democracy, focusing on the Middle East and the broader Arab-Islamic world.

How does your positionality as a Canadian of Iranian descent shape your work as director of the Center for Middle East Studies?

My ethnic background as a child of immigrant parents gives me a foot in both worlds - a foot in the world of my parents and larger extended family, which is rooted in the Middle East, and a foot in the Western world where I grew up. The second part of the answer is that my background in Canada gives me a more global perspective and sensitivity to, and understanding of, the problems of our world that often gets lost in the United States by an audience that is very much focused on US national security concerns and debates which are a byproduct of America's superpower status. While I am deeply ensconced in US foreign policy debates, I am also aware of and deeply sensitive to non-Western perspectives on global problems, especially those emanating from the Global South.

What advice would you have to students, activists, and policymakers in terms of building solidarity between North and South?

Always exercise humility. Do not presuppose you know the answers in advance in terms of how to help people in other parts of the world who are struggling for dignity and democracy. If you are serious about solidarity work and really want to make a difference, you have a moral imperative to first consult with people on the ground in the Global South and ask them for guidance on how to best help them in their struggles. My rule of thumb for international solidarity is to follow this framework. Always consult with organically connected grassroots activists and actors in the Global South. Take your cues from them and seek guidance from those on the frontlines of the battle before initiating acts of solidarity.

Copyright ©2025 University of Denver | All rights reserved | The University of Denver is an equal opportunity institution