EXTENDED! CO residents can apply FOR FREE through December 1st. Apply now!

Secure your scholarship offer in just 2-3 days through December 17! Get started.

No waiting. No guessing. Join us for Instant Decision Day on December 3. Register now.

EXTENDED! CO residents can apply FOR FREE through December 1st. Apply now!

Secure your scholarship offer in just 2-3 days through December 17! Get started.

No waiting. No guessing. Join us for Instant Decision Day on December 3. Register now.

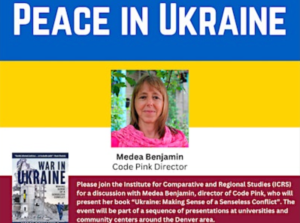

On April 4th, ICRS hosted peace activist and Code Pink founder Medea Benjamin. Listen here for a short conversation with ICRS Director, Aaron Schneider.

Leaders of four prominent U.S. think tanks came together last week to take part in a discussion about civil discourse, diverse perspectives and the role of disagreement in a healthy democracy.

The event was the first of the University of Denver’s Denver Dialogues, a series of virtual conversations with experts from the American Enterprise Institute, Aspen Institute, Hoover Institution and New America meant to spark respectful and constructive conversations about world and national events.

University of Denver Chancellor Jeremy Haefner introduced the event by underscoring the importance of engaging authentically and respectfully when challenging evidence-based ideas and presented Denver Dialogues as a way to engage with complex topics as an academic community.

“Since my inauguration as Chancellor, I have committed the University of Denver to be a beacon for intellectual curiosity: for free speech, academic freedom and thought pluralism,” Haefner said. “We do this—and we affirm these values—because they are critical and central to the functioning of democracy.”

The conversation featured former U.S. Secretary of State and current Director of the Hoover Institution Condoleezza Rice, a well-known graduate of the University of Denver. Additional panelists included Robert Doar, president of the American Enterprise Institute; Dan Porterfield, president and CEO of Aspen Institute; and Anne-Marie Slaughter, CEO of New America.

Josef Korbel School of Global and Public Affairs Dean Fritz Mayer and Scrivner Institute of Public Policy Director Naazneen Barma moderated the discussion.

Mayer initiated the discussion by commenting on the importance to democracy of everyone, including those whose political positions do not eventually prevail, accepting the results of referendums on those positions.

“It’s hard to think of a more important issue in this country and, indeed, around the world, than the deterioration of the civic culture on which democracy depends,” Mayer said. “A fundamental requirement of a democracy is that, while we may disagree vehemently about what is to be done, we accept the legitimacy of those with whom we disagree.”

Before opening the floor to the think tank leaders, Barma emphasized the purpose of Denver Dialogues: to model difficult yet respectful conversations about tough subjects for the DU and Denver communities.

“One of the Scrivner Institute’s central mandates is to serve as a hub for conversations on public policy and the collective good,” she said. “The Denver Dialogues will bring substantive policy conversations to our campus and our broader community, while modeling approaches to constructive debate.”

So, what is the nature of the problem when it comes to dwindling civility in public discourse?

Rice said it comes down to information echo chambers.

“We get our information in groups—affinity groups, which we feel very comfortable [in],” she said. “I can, today, go to my website, I can go to my aggregators, can go to my cable news channel. I never have to actually encounter anyone who thinks differently.”

Rice said the opening of hearts and minds to others’ points of view will allow civil discourse to blossom.

Slaughter echoed Rice’s negative view of hive-mind communication.

“Even if we were disposed to listen, we are not in spaces where we are being exposed to people who disagree with us, in a way that allows us to talk, rather than shout, or simply defend,” she said.

Slaughter offered up a valuable lesson: You can’t persuade unless you’re willing to be persuaded.

“And that means coming at any discourse, or dialogue, or conversation with an open enough mind to think, ‘I’m listening and I’m willing to change my mind,’” she said. “Maybe not my core principles, but I’m listening and willing to let you persuade me, and in return, you’re more likely to let me persuade you.”

The think tank leaders urged DU community members to see themselves not just as red or blue—to think about people as more than their policy stances.

Doar placed the blame for increasingly volatile conversations on the growing polarity of political parties.

“We’re retreating to our corners, and the fringes are dominating the dialogue—and the social media world exacerbates that by feeding into and promoting the most angry responses from people that participate in that,” he said.

“I would want to particularly compliment you guys at the University, because I believe part of the problem is on our college campuses … there hasn’t been sufficient viewpoint diversity, and there has been too much shutting down of people who say things that are contrary to the prevailing view,” Doar continued.

Dan Porterfield argued that the problem lies within the human spirit itself.

“We are the problem,” he said. “Because all humans have a tendency to gravitate toward what makes us comfortable or move away from what we fear. This is one of the things we all have to learn, in our schooling, in our family upbringing—how to deal with our vulnerability in such a way it doesn’t prevent us from engaging with others.”

For more information about Denver Dialogues and upcoming events, visit the series website here.

Since January 2021, according to the Gun Violence Archive, the United States has had 15 mass shootings with more than four victims. One such tragedy in Boulder, Colorado, claimed 10 lives. Each mass shooting is invariably accompanied by calls for thoughts, prayers and even reform. But despite the constant shootings, suicides and domestic gun violence, political remedies remain mired in controversy, and Americans continue to lose their lives.

In an effort to address what President Joe Biden has called a gun violence public health epidemic, the Josef Korbel School of Global and Public Affairs recently hosted U.S. Rep. Diana DeGette and former Colorado State Rep. Cole Wist for a dialogue on gun reform and control. The event marked a new partnernship between two University of Denver institutions: the Korbel School’s Scrivner Institute of Public Policy and the Center on American Politics (CAP).

The DU Newsroom asked Scrivner director Naazneen Barma and CAP director Seth Masket to discuss gun reform from both the policy and political perspectives. The conversation has been edited for clarity.

How should we understand the problem the U.S. faces with gun violence? Is the problem isolated to mass shootings, and will gun control alone solve the issue?

Barma: Mass shootings are horrifying, and banning assault-style weapons is one necessary step to limit the number of deaths from such events. But gun-related violence in the United States is about more than these mass casualty events, which account for 2–3% of gun deaths. About 40,000 Americans die each year from gun violence, more than half from suicide involving guns, and the balance mostly accounted for by urban gun violence and domestic partner-related gun violence. Extreme-risk protection laws like Colorado’s red flag law, which allows a judge to remove a person’s firearms if they are a danger to themselves or others, can go some way toward saving lives from gun violence. But reducing gun deaths is also a task for improved social services and more engagement from public health agencies that can take on things like better public education about gun safety (just like public education about seatbelts and safe driving) as well as better training for gun owners.

What lessons can the United States learn from countries that have enacted gun reform? Who should policymakers be looking to as examples?

Barma: Both Australia (in 1996) and New Zealand (in 2019) enacted gun control legislation in the aftermath of mass shootings — [legislation] that banned automatic and semiautomatic weapons and confiscated those firearms via mandatory buyback programs. Why hasn’t an emphatic response like that materialized in the aftermath of any of the horrific mass shootings over the past two decades in the U.S.? The answer lies in some combination of the unique political setup in the U.S. — the power of the pro-gun lobby, the effects of political polarization and the constitutional right to bear arms. The United States has a unique gun problem among industrialized countries. Gun ownership here is almost four times higher than in the next most gun-owning developed countries; and gun-related homicides are on an order of magnitude higher in the U.S. than in other countries.

How might research and academia advance the conversation around gun violence and gun control? Can the political process alone fix this problem?

Barma: Federal funding for gun-related research was reinstated earlier this year for the first time since 1996, when the U.S. Congress, at the behest of the National Rifle Association, passed the Dickey Amendment and prevented federal funds from being spent on gun control-related studies. For 25 years, we have suffered greatly from a dearth of evidence on gun violence and potential prevention measures. New research will be crucial in evaluating the impact of the range of gun control and other gun safety measures in place and formulating informed, evidence-based policies — and, hopefully, even nudging the political process — to reduce gun violence moving forward.

How can we understand the politics of gun reform and gun violence in the United States? Have we reached a place in the U.S. where politicians can pursue meaningful change in a bipartisan way, or are we still too divided?

Masket: The political parties are deeply divided on guns, probably as much as they’ve ever been. It was once fairly common to see rural Democrats who supported gun access and urban Republicans who supported restrictions. That’s very rare today. But just because the parties are divided doesn’t mean change can’t occur. Recently, the U.S. House passed two bills to expand and lengthen background checks. Nearly all Democrats and just a handful of Republicans voted in support, although it’s not clear whether these will pass the Senate. But increasingly Democrats have been more supportive of gun restrictions, making it more likely that some will pass when they control Congress.

How do Americans really feel about gun violence and gun control? Is the general population as divided as politicians seem to be on this issue?

Masket: Americans are deeply divided on guns, reflecting the parties to which they belong, although they’re not nearly as polarized as elected officials. Also, Americans overall tend to be more favorable toward gun control than Congress is. According to a recent Pew survey, a narrow majority of 53% said that gun laws should be more strict across the country, and only 14% said they should be more relaxed. If you break that down by party, some 81% of Democrats said gun laws should be more strict, but only 20% of Republicans agreed with them. That’s a large divide. On the other hand, on a recent vote in the U.S. House on background checks, 99% of Democrats voted in favor, while only 1% of Republicans did.

Can we expect real federal action on this issue anytime soon? How is this figuring in the political agenda at a national level?

Masket: Most of the action we’ve seen on gun reform in recent years has happened at the state level, but those have moved in different directions. Colorado, along with other blue states like Virginia and Maryland, has recently passed some gun ownership restrictions, while red states like Texas and Iowa have worked to make it easier for residents to own and carry firearms. But even if states were mostly moving in the same direction, that probably wouldn’t be sufficient — it’s easy to move weapons across state lines, even to states where it’s difficult to buy them.

There has been some federal action, but it’s very limited right now and very conditional on which party controls Congress. And party control of Congress has jumped back and forth a good deal in recent years and may flip again next year. What’s new, though, is the examples set by the states. Several prominent politicians have embraced gun control without it ending their career, which is something many in the political system have feared. John Hickenlooper is a great example of this. He was a reluctant supporter of gun control as governor in 2013 but ultimately embraced it, and last year he was elected to the Senate by nearly 10 points.

“First we start with building a scenario that tries to represent a continuation of all of the things you would expect to see if the world continued as normal,” says Jonathan Moyer, explaining his work with global development modeling. “The next question is ‘Well, what would disrupt that trend?’”

Moyer says a pandemic is always one possible answer to that question. Today, of course, it is a reality.

That reality has completely reshaped Moyer’s work as an assistant professor in the University of Denver’s Korbel School of International Studies and director of the Frederick S. Pardee Center for International Futures. Founded in 2007, the Pardee Center works to improve the human condition through long-term forecasting and global trend analysis. Much of the center’s research revolves around the International Futures (IFs) modeling system, a free, open-source software developed by Barry Hughes, the Pardee Center’s founding director. Today, the center is home to 15 full-time staff members and an additional 60 research aids.

While some think of the Pardee Center’s work as peeking into the future, Moyer says it’s more about creating an understanding of what the future might look like under different conditions. This is especially true with COVID-19.

“Some people want to predict the pandemic. How long is it going to last and how many people will die? That’s not what we do,” he says. “Instead, we are sitting back and saying, ‘OK, what would the pandemic have to change and at what magnitude in order to see an effect on human development over the long term?”

The Pardee Center’s work over the last year shows that the ramifications of COVID-19 will be felt well into the future, particularly for fragile regions on the brink of major development, like Sub-Saharan Africa.

Pardee Center scenarios depicting the most likely outcome of the pandemic show an additional 50-100 million people falling into extreme poverty in the wake of reduced economic activity and global lockdowns. But with a global pandemic comes uncertainty, and that uncertainty, Moyer says, could push us toward the worst-case scenario, in which the virus continues to mutate, vaccines rollout too slowly and extreme poverty rates increase beyond our imagination.

But there’s also a best-case scenario — a chance for a global shift for the better.

“Now the positive story is that this COVID crisis is an opportunity to recognize that the world is full of shocks and things we can’t anticipate,” Moyer says. “The best way to prepare for them is to help poor and vulnerable governments and populations improve their capability to respond to shocks. … If you do that, and you do it carefully, you can actually improve development and make things better than they would’ve been in the absence of the crisis.”

As the world continues to watch the economic impacts of the pandemic, the team at the Pardee Center is also keeping a close eye on global conflict. One of its early pandemic reports forecasted the possibility of 13 new conflicts by 2022, which would bring the world back to the instability of the early ‘90s. While that hasn’t quite come to fruition, Moyer says, increasing conflict is still a likelihood, particularly in areas where lagging infrastructure has prevented a robust government response to the pandemic.

“If you have countries with poor abilities to respond to the needs of the citizenry, that can lead to additional conflict because then you have groups of people in the country who compete for power and you get internal coups or civil conflicts,” he explains. “Because the pandemic has a big negative effect on the economy, that could spill forward and negatively affect government’s abilities to earn revenue, to provide security or services, health and education. That kind of a shock can cause populations who are not happy to revolt.”

While it’s still unclear how exactly the chips will fall, one thing is certain: The pandemic’s impact on sustainable development will be significant in one direction or the other. And it’s not just the economy and conflict. Things like food insecurity, gender dynamics, childhood development, China’s rapid rise as a global power and more are being closely watched by the Pardee Center researchers.

Yet even with sophisticated tools and deep knowledge of development, so much remains uncertain. That’s par for the course, even outside of pandemic times, says Moyer.

“Uncertainty is a certainty, and you have to live within that. But that’s also why what we do is helpful,” he says. “You can’t get rid of it, you can’t wish it away, but you can provide yourself with the proper knowledge that you can use to make better decisions.”

Grace Wankelman didn’t mean to start a movement. When she teamed with Shannon Saul (BA ’20) and Madeline Membrino, a rising fourth-year student at the Josef Korbel School of Global and Public Affairs, urging the University of Denver to “do better” addressing and preventing sexual assault, all she wanted was to be heard.

Turns out, she did both.

From the minute it launched in January, the @wecanDUbetter Instagram account made waves with a stream of graphic stories detailing on-campus sexual harassment, sexual assault, gender violence and the toll these took on survivors. Within hours, the account had more than 1,000 followers. Within weeks, DU Chancellor Jeremy Haefner responded with a seven-page action plan to address the concerns.

“I felt like it was one of the first times our university has engaged in a really productive conversation on gender-based violence that was centering the survivors’ stories,” says Wankelman, who is majoring in political science, economics and international studies. “We saw so much progress, from student engagement to faculty and clubs. DU’s administration really responded well, especially the chancellor with the response we got and the change we’ve seen happen on DU’s campus. It was truly powerful, and it was a moment where so many people felt like they had a voice. And a lot of people from other campuses across the country started reaching out to us, because they were seeing this and the change that we were able to get.”

In February, wecanDUbetter became, simply, Do Better, an organization serving institutions nationwide. The site’s creators wanted — and needed — to grow, Wankelman says. They needed, a classmate told them, to look into Project X-ITE. The on-campus resource for startups and student entrepreneurs could provide the boost the team needed to amplify their message.

Specifically, Wankelman says, they zeroed in on the XLR8 program. Formerly known as Pioneering Summer, XLR8 is a 10-week intensive experience dedicated to developing fledgling ideas and teaching students what it takes to be successful in the business world.

“Whenever I think of business, I didn’t think of it as a space for me or for our organization,” Wankelman says. “I 100% believed in our mission and our organization, but I saw all of these badass businesspeople pitching incredible ideas. It seemed like they knew how to run a business, and we were very different from them.”

The team nailed its pitch, gained acceptance into the program and came under the wing of Nina Sharma, Project X-ITE’s executive director.

“I think they are the best example of how anyone can be an entrepreneur,” Sharma says. “If they see a problem in the world that they want to fix, they can fix it. That makes them entrepreneurs. I love that they’re changing what the definition is and what an entrepreneur looks like.”

Do Better is the first nonprofit to enter the four-year-old XLR8 incubator, which took on 19 students from eight companies this year. Each startup receives $10,000 to develop their idea. Over the course of the summer, the teams attended 25 different workshops on everything from branding to fundraising to organizational development.

Every step of the way, students work with mentors from the Denver business community and grow together in a collaborative cohort environment — even though that had to happen virtually this year.

That made it hard, Sharma says, to have the in-person get-togethers and spontaneous bonding that is a hallmark of the program. But conversely, a Zoom-centered curriculum provided access to professionals around the world.

Wankelman and Do Better used some of the sessions to connect with specific resources for nonprofits.

“The biggest thing we’ve emerged with is how can we turn this movement or moment into a sustainable organization that can support itself,” Wankelman says, crediting this result to new financial and business plans.

Do Better is working to establish satellite organizations on other campuses while working with university administrations to ease communication and foster collaboration. Its founders are seeking and have participated in speaking engagements at conferences and other gatherings. The nonprofit, close to acquiring its 501(c)3 status, is also exploring ideas for fiscal sponsorship and fundraising.

From Sharma’s point of view, Do Better’s most important work was growing together as a team. Unlike most of the startups, which are created by friends or classmates, Do Better grew out of a shared experience that pulled Wankelman, Saul and Membrino together. They had hardly met before wecanDUbetter launched and began to garner headlines.

“They got thrown into this work, but they didn’t actually know each other personally,” Sharma says. “A lot of their growth was getting to know each other, getting to really understand each other as people, how they work differently together and what different skills they brought to the table.”

Despite the labor of starting a nonprofit — not to mention the emotional work that comes with such personal advocacy — Wankelman feels more empowered than ever to grow Do Better. She’s inspired by the feedback the organization has already received, much of it from survivors who finally feel heard and able to report their experience or speak out.

With the XLR8 experience in her toolbox, Wankelman feels she’s found her voice, too.

“After working with XLR8, I’ve realized that I do have something to say; I have the ability to make change, and I can be a leader in this space,” she says. “In the past couple of months, I went from this place of absolute hopelessness and powerlessness to a space where we’re working with so many inspiring people and we’re seeing the actual change.

“Understanding what it feels like to have absolutely no power and all of your autonomy taken away from you — not only to reclaim it for yourself but to help other people find that, I would be willing to work 25 hours a day to do that.”

In 1950, 30 percent of the global population was European. By 2030, 30 percent of the global population will be African.

“That’s a huge transformation. An extra billion or so people,” says Jonathan Moyer, director of the University of Denver’s Frederick S. Pardee Center for International Futures. “It means huge changes in the global system, and people should be aware of them and the magnitude of these changes.”

Massive shifts like these present formidable questions — ones which Moyer and his team of researchers at Pardee aim to help answer. In fact, this is the very mission of the center, created in 2007 to improve the human condition through long-term forecasting and global trend analysis.

The trajectory of Africa’s demographic shifts and other transformations are outlined in a recently released report prepared by the Pardee Center in collaboration with African Union Development Agency (AUDA-NEPAD), which serves as the development arm of the African Union. The report was launched by the AUDA-NEPAD in Addis Ababa in front of influential figures in African politics, including Vera Songwe, head of the United Nations Economic Commission for Africa.

The Pardee Center’s supporting role with the AUDA-NEPAD dates back to 2012 and promises to extend well into the future. “We are in conversations to formalize the partnership in a more concrete way,” Moyer says. “Our role is to sit back and wait for guidance and instructions from them, because they are setting the agenda and we are filling a gap in that technical space.”

Moyer hopes that the report will help guide the AUDA-NEPAD in its decision making over the next 50 years. “We want to build capacity to do analysis using the tools we have here to help continental, regional and national governments better plan for development and to make choices that prioritize human capability improvements within the context of environmental sustainability,” Moyer says. “That’s the goal.”

Pardis Mahdavi, acting dean of the Josef Korbel School of Global and Public Affairs, home to the Pardee Center, considers this pairing of research and application critical to the school’s mission. “The Pardee Center’s partnership with the African Union Development Agency is an excellent example of the Korbel School’s broader mission to bring academics and policy makers to the same table, and to marry research to real-world applications and solutions,” she says. “We're striving to break down the walls between academics and practitioners, and this partnership is a good model for how this works. For our students, it's a unique opportunity to see how what they learn in the classroom plays out across the globe.”

While predicting the future seems tricky, Moyer is confident Africa will see transformations in four areas, all discussed in the report: demographics, human development, technology and natural systems. “Some things are more certain than others,” he says. “The demographic future is pretty certain. The massive population growth is happening. … Human development is happening —that’s persistent. Education will improve. Life expectancies will improve. Renewable energy growth is a persistent trend. The fact that climate change is happening is a persistent trend.”

All of that exists within a framework of uncertainty, of course. Governance and choice remain unpredictable as ever, presenting a true wild card that could vastly impact the country’s trajectory. And, with a booming population comes challenges related to education, health care and infrastructure. What’s more, just as technological advancements like cell phones and ATMs can improve lives, others, like automation and robotics, threaten to reduce the number of jobs, even while accelerating development.

“Being aware of the big transformations that we are highlighting is important, but then also understanding that building government capacity, improving transparency and effectiveness, improving inclusion — these are all important drivers of the future of the continent,” Moyer says. “Political decision makers, civil society and citizens will make the decision about where to go, so we are meant to play a background role in this space.”

Without a doubt, though, says Moyer, Africa is a power on the rise. “Africa is going to be a giant economic block and a giant demographic block,” he explains. “There’s a huge amount of uncertainty still, but Africa will be bigger, wealthier and more developed.”

And, Moyer adds, it has a slight competitive edge when it comes to sustainable development: “There isn’t another region that developed with a continental organization like the AUDA-NEPAD that’s trying to help guide the development. This is completely unique.”

The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) recently featured the International Futures (IFs) modeling system in their report, "Getting to Zero: A discussion paper on ending extreme poverty." The study cites forecasts from the Frederick S. Pardee Center's first Patterns of Human Progress (PPHP) volume, "Reducing Global Poverty," authored by Barry B. Hughes, Mohammod T. Irfan, Haider Khan, Krishna B. Kumar, Dale S. Rothman, and José R. Solórzano. See page two of the USAID report to see how our IFs forecasts from 2009 stack up against others.

Other News/Blog Posts from the Pardee Center:

February Updates from the Pardee Center

Happy New Year from the Frederick S. Pardee Center for International Futures

Copyright ©2025 University of Denver | All rights reserved | The University of Denver is an equal opportunity institution