90% of applicants who apply by the priority deadline receive scholarship support. Apply now!

Now accepting applications for Fall 2026. Apply now!

Menu

Menu

90% of applicants who apply by the priority deadline receive scholarship support. Apply now!

Now accepting applications for Fall 2026. Apply now!

On March 11, 2021, Pardee Institute Research Scientist Willem Verhagen, Assistant Director of Analysis David K. Bohl, and Director Jonathan D. Moyer along with center partner and former Research Aide Stellah Kwasi published a piece in ISS Today that was featured by The Daily Maverick titled, "Covid-19 may increase trade between Africa and China to the detriment of the EU and US." The piece may be accessed here.

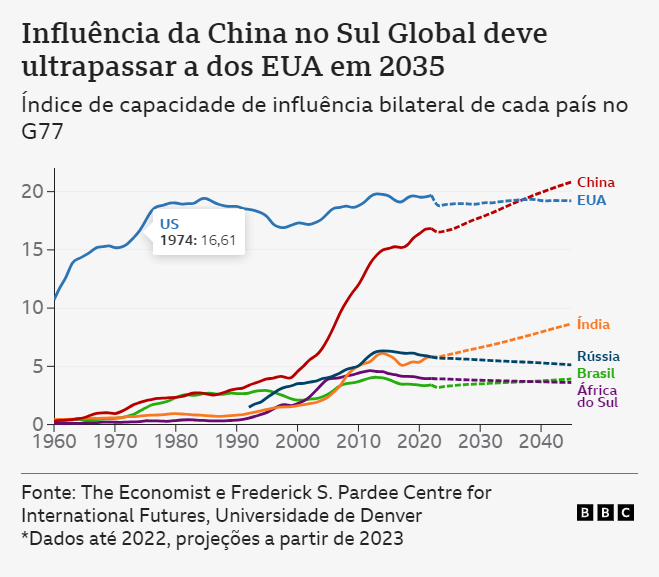

A recent report published in the Economist, which utilized Pardee Institute’s Formal Bilateral Influence Capacity Index (FBIC) data to compare the level of influence of some countries among the members of the G77, has inspired another article by BBC Brasil. The piece titled “Who competes with Brazil for leadership of the 'Global South” delves into the dynamics of influence within the Global South, focusing on Brazil's role and its competitors.

The FBIC data influenced BBC Brasil's analysis of how Brazil positions itself as a leader among developing nations and leverages its economic, political, and cultural ties to assert influence. Observing Brazil’s strategic partnerships and initiatives aimed at strengthening its leadership status.

Additionally, the article compares Brazil's influence with that of other emerging powers, such as China, India, and Russia who also compete for leadership within the Global South.

Prominent publications like The Economist and BBC Brasil Pardee citing the Pardee Institute’s FBIC data highlights the tool’s relevance and utility in understanding global dynamics, grows the Institute’s contribution to the field of international studies, and affirms the importance of the Institute's research in informing public discourse and policymaking.

RadioEd is a biweekly podcast created by the DU Newsroom that taps into the University of Denver’s deep pool of bright brains to explore new takes on today’s top stories. See below for a transcript of this episode.

Lions and tigers and panda bears, oh my! By the end of the year, all of the United States’ giant pandas will be returned to China. But why?

In this episode, Emma tackles the current state of U.S.-China relations with the help of Suisheng Zhao, a University of Denver professor and the executive director of the Center for China-U.S. Cooperation in the Korbel School of International Studies. Emma also examines the future of the relationship between the two world powers with Collin Meisel, the associate director of Geopolitical Analysis at the Pardee Center for International Futures.

Suisheng Zhao is a professor and Director of the Center for China-U.S. Cooperation at Josef Korbel School of Global and Public Affairs. He is a founding editor of the Journal of Contemporary China, and a member of the Board of Governors of the U.S. Committee of the Council for Security Cooperation in the Asia Pacific. Zhao received his Ph.D. degree in political science from the University of California-San Diego, M.A. degree in Sociology from the University of Missouri and BA and M.A. degrees in economics from Peking University. He is the author and editor of more than ten books and his articles have appeared in Political Science Quarterly, The Wilson Quarterly, Washington Quarterly and more.

Collin Meisel is the Associate Director of Geopolitical Analysis at the Pardee Center. He is also a subject matter expert at The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies and a Nonresident Fellow with the Strategic Foresight Hub at the Stimson Center. Meisel’s research focuses on international interactions and the measurement of the depth and breadth of political, diplomatic, economic, and security ties between countries as they have and are projected to evolve across long time horizons. Meisel is a U.S. Air Force veteran. He holds a Master’s in Public Policy from Georgetown University. His research has been published in the Journal of Contemporary China, Journal of Peace Research, and Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression, and his commentary has been published by Defense One, The Hill, the Modern War Institute at West Point, and War on the Rocks, among other outlets.

“Say goodbye to the pandas: All black-and-white bears on US soil set to return to China”

“Smithsonian’s National Zoo Hosts Panda Palooza: A Giant Farewell, Sept. 23 to Oct. 1”

Council on Foreign Relations: “U.S.-China Relations Timeline”

Council on Foreign Relations: “Why China-Taiwan Relations Are So Tense”

Emma Atkinson:

You're listening to RadioEd, the University of Denver podcast. I’m your host, Emma Atkinson.

It’s a bear bummer. A mammal misfortune. A panda predicament.

You know what I’m talking about? By the end of this year, all of the giant panda bears loaned to U.S. zoos by the Chinese government will return to China.

The move will leave the U.S. panda-less for the first time since 1972.

And people are pissed! They’re sad to see the sweet, bumbling bears go. Who wouldn’t be? The National Zoo in Washington, D.C. hosted a “panda-palooza” event last month, a goodbye party of sorts for their three pandas.

According to the Smithsonian, the study of giant pandas at the National Zoo has produced invaluable information about panda nutrition, behavior, genetics and more. The care of pandas by zookeepers there has even served as a model for the management of other endangered species.

So why is this happening? Why now? It might be overkill to call the pandas pawns in the chess game that is U.S.-China relations, but it is fair to say that “Panda-gate” is a symptom of the deteriorating relationship between the two world powers.

In this episode, I’ll speak with two experts from the University of Denver—Suisheng Zhao and Collin Meisel—about the Chinese-American relationship and what the future holds for the two countries.

The story of the U.S. and China is a long and complicated one. The People’s Republic of China was established in 1949, and since then, China and the U.S. have gone through periods of both peaceful reciprocity and downright discord.

The University of Denver’s Korbel School of International Studies has long been interested in studying the complexities of U.S.-China relations. SWEE-sun Tsao is a professor in the Korbel school and the executive director of DU’s Center for China-U.S. Cooperation. He’s also the Editor of the Journal for Contemporary China, “the only English language journal edited in North America that provides exclusive information about contemporary Chinese affairs for scholars, businesspeople and government policymakers.”

With an expert right on campus, I talked with Zhao to get a better understanding of what the pandas signify. He says, in recent history, we’ve seen the Chinese-American relationship yo-yo between both ends of the spectrum.

Suisheng Zhao (02:12):

I came to the US almost 40 years ago and have witnessed the dramatic changes in the relationship. In fact, I will say I benefited from that relationship, because for many years, the engagement on the U.S. side and cooperation on the China side really kept the relationship in a very healthy [state] to benefit both China and the U.S.

Emma Atkinson (02:47):

Zhao says he believes the current breakdown in the U.S-China relationship began in the second term of the Obama administration and was only worsened by President Donald Trump’s policies toward China, including a set of tariffs worth at least $50 billion in March 2018. China imposed retaliatory measures, thus setting off a trade war of sorts, with the two countries exchanging tariffs on goods from Chinese clothing and electronics to U.S. agricultural exports.

He says that communications between the two countries broke down during the Trump administration, leading to misperceptions and misjudgment. And now, under Biden, we’re seeing efforts to reopen those channels.

Suisheng Zhao (03:23):

These communications basically started in the summer. This summer, we saw four U.S. Cabinet members visit Beijing since June, starting with Secretary of State Tony Blinken, and then we had Treasury Secretary Yellen, and then we had John Kerry, the Climate Special Envoy, and then we had the Secretary of Commerce. And we now currently have the Senate delegation led by the majority leader, Chuck Schumer, and Chuck Schumer, he just met with Chinese President Xi Jinping and this morning and met with the Chinese foreign minister, and simply had some kind of very candid, and I will say also constructive meetings.

Emma Atkinson (04:24):

But Zhao says despite the two countries talking the diplomatic talk, he has yet to see them walk the walk when it comes to concrete policies.

And the problem with U.S.-China relations, he says, can be attributed to three factors. The first is a fundamental difference in political ideology.

Suisheng Zhao (04:41):

China has become increasingly authoritarian, totalitarian in my lifetime. In fact, I came to the U.S. almost 40 years ago, when China began to open up to reform and gradually tried to integrate into the international economy, and also to open up even the political peripheries of the system. And so I could travel back and very frequently; I met my colleagues in China, talking about how to help them to understand international society and to work with the international community. But I found this has been changed dramatically, reduced dramatically. China has gradually closed up, closed down.

Emma Atkinson (05:29):

The second issue causing friction between the U.S. and China is the unavoidable tension between an incumbent global power—the United States—and a rising power—China. Zhao says since its rise to international dominance following World War II, the U.S. has been reluctant to void any of its global influence to other countries—and that includes China. And China, on the other hand, will do anything in its power to claw its way up the global leadership ladder.

Suisheng Zhao (05:53):

USA will do everything to keep its promising American words, global leadership, and will not allow China to repress it. And China, on the other hand, on the rising side, for many years, China would think that the U.S. would do everything, to suppress China. And so it will do everything to keep America at bay try to do everything to keep its rising momentum. So this can have structural conflict.

Emma Atkinson (06:29):

And the third issue, of course, is the problem of Taiwan, officially known as the Republic of China. Taiwan was transferred from Japan to the Republic of China after World War II, and though it has been governed independently since then, China, known as the People’s Republic of China, views the island as part of its territory.

The idea that Taiwan is part of China is called the “One-China Principle,” and the U.S. recognizes this as its official policy on Taiwan. However, the U.S. has committed to selling arms to Taiwan for self-defense, which could ostensibly be used against China in the event of an invasion. The Council on Foreign Relations calls the United States’ position on Taiwan one of “strategic ambiguity.”

But President Joe Biden has said multiple times that the U.S. would, in fact, come to Taiwan’s defense in the event of an attack by China. Some experts say that the Taiwan issue could be a major factor in—and perhaps the catalyst for—a war between the U.S. and China.

Zhao says this is perhaps the most difficult sticking point between the two countries and agrees that the Taiwan issue is one that could cause them to come to blows.

Suisheng Zhao (07:35):

Well, for China, this is a commitment to war and is clearly giving up of the so-called “strategic ambiguity…” U.S. will defend Taiwan. Then, a nuclear power—China—and a nuclear power—U.S.—could possibly come to a war directly over Taiwan. This is the only issue, in fact, that could potentially bring these two nuclear powers into military conflict, and neither side has any intention to accommodate, to compromise on this issue.

Emma Atkinson (08:23):

Some experts and commentators have called the state of U.S.-China relations the “new Cold War.” Zhao disagrees with this—he says there are too many other countries with significant influence, like Japan and Australia, that haven’t explicitly taken sides in the U.S.-China brouhaha. He says this perception of “Cold War”-like relations comes from people’s misunderstanding of the situation—and from an overreaction.

Suisheng Zhao (08:46):

China is more afraid of American liberal democracy than America is afraid of China. Think about that.

Emma Atkinson (09:03):

So what’s next? We’ve got three issues that the U.S. and China refuse to budge on. How might this affect their relationship moving forward—and what does it mean for the rest of the world?

To find out, I spoke with Collin Meisel, associate director of Geopolitical Analysis at the Pardee Center for International Futures. The Pardee Center, among other things, uses the International Futures model to make forecasts about what will happen among global powers in the coming years.

Collin Meisel (09:29):

So in the work that we do, we have a global focus, right. So when we gather data, often we're gathering data on 180 895 200 plus countries over long time horizons. And so we think that it's important to have just as good of an understanding of Zambia as a country like China. That said, given its presence in sort of diplomatic relations worldwide, economically security, security related interactions, increasingly, China's very, very important, obviously. And so while we have a global focus, often the conclusions that we draw, or the analysis that we conduct gravitates toward China. And so one thing that has been of particular interest to our funders, but also to us, in general, is sort of what is China's role in the international system? How has that changed in the past? And how do we expect that to change in the future? And what does that mean for the US role in the world? Are we moving toward a new Cold War, bipolar international system? Are we moving to towards something new, maybe a multipolar international system where the US and China are just too important powers among many? Those are the questions that we're interested in and asking and doing our best to answer, although there are no perfect answers.

Emma Atkinson (10:42):

So how have you applied that model to what's going on with China? And you know, if you could give me some of those predictions?

Collin Meisel (10:48):

So one, one qualification, we often use the word forecast instead of prediction. Prediction sometimes implies to some that you're trying to make a specific point prediction about what the future will be. So an example would be in the year 2050, US global gross domestic product will be you know, X trillion dollars. And while our tool the international futures tool does have a current path prediction, we call it a forecast because we're interested in general trends and then we also conduct alternative scenario analysis where we say what if something else happens. So forecasting is more about understanding general pressures and and trends across various categories and how they interact various various things like human development and growth and and conflict and climate change and all of these things together. And so forecasting is more about understanding systems and relationships than it is about making sort of crystal ball assessments about exactly what will happen.

Emma Atkinson (11:47):

Much of Meisel’s work looks at the balance of power between the U.S. and China and attempts to forecast what that relationship will look like over the next century. He says that in 80% of the 29 theoretical scenarios the Pardee Center team ran, China ended up overtaking the United States as the leading global power.

Collin Meisel (12:06):

one thing I'd like to add to that is that whether China passes the US doesn't actually matter. And it gets to prediction versus forecasting. One thing that is consistent across all scenarios, is that the gap and relative power in the world between the US and China is shrinking. And we expect it to continue to shrink. And so China will be important. And because that gap and power is shrinking, it probably unfortunately means that there will continue to be US China tensions because China is going to want to likely continue to assert its its own policy preferences and the international system just as the US did when its power rose, and the US is unlikely to want to sort of give up the mantle of being the world leader, you know, that we've had for most of my lifetime.

Emma Atkinson (12:51):

And even if Meisel’s forecast is wrong, even if China doesn’t end up passing the U.S. as the world’s leading power, he says that the relative gap in power between the two countries likely will continue to close.

Emma Atkinson (13:04):

What are you pretty sure is not going to happen?

Collin Meisel (13:06):

What I am pretty sure is not going to happen is I do not think, barring exceptional, highly unexpected events, that we will return to a unilateral unipolar world system that we saw with the US after the collapse of the Soviet Union, where there really was no rival power, and the US could sort of do mostly what it wanted. I don't see that happening again, in my lifetime, neither for the US nor China. Right. As China's power rises, our forecasts show that we don't expect China to reach the point that the US reached in early 1990s. Right, so it's not like, we're just going to see a shift from one pole to the next. I think that's one thing I'm fairly certain about now.

You know, predictions are difficult, especially about the future. Right. That's the famous quote. And so, of course, there are things that could happen. A, an endemic disease that disproportionately affects, you know, the US, but for some reason doesn't escape our borders. Right? I don't think that that's likely, I guess it's possible. They're probably sci fi books about it. The collapse of the Chinese Communist Party is that's what some people have predicted time and, again, wrongly so far. If that were to happen, and China were to sort of go into disarray. Meanwhile, somehow Russia and Ukraine tensions decrease, and Russia sort of is happy with its own sphere and doesn't try to expand its global influence.

I mean, there's potentially a world where, yes, that the US has this relative rise. And we could go back to that moment. But I just, I don't see that happening. And I don't think that's a world that we want, right? I don't think we want a country of 1.4 billion people failing to the point where all of its people are suffering, and you're seeing de-development.

Emma Atkinson (14:53):

That's, that's a very good point. And I think something that is often forgotten in discussions like this is the humanization of, of what it means for a country to be powerful or to fall from power. Right? So I'm really glad you brought that up. we've been over this in a more academic sense, but let's just say I'm a regular Joe, don't really watch the news, you know, have a basic understanding of what's going on, just like hearsay like, ‘Oh, I know, things between China and the US aren't very good.’ Explain to me, in the most simplistic of terms, what your forecast is for the next 25 years?

Collin Meisel (15:28):

Yes. So I would say I would start with the world is changing. And that's okay. The the US has, for my lifetime, been the world's leading power. And we've sort of been the star of the show. And that appears to be changing. I think we've already seen it in our everyday lives. And we're likely to see it more and more, right where the US is not necessarily going to be able to step in and get his way anywhere in the world at any point in time.

Increasingly, we're going to see other countries, China in particular, act in ways that maybe we from an American perspective might find upsetting. And in some ways, we will be able to shave and shove and influence that behavior and other words we want. In some ways, that's going to be a challenge that we will need to rise to and figure out how to do that right, cooperating more with other countries that maybe we would have ignored And in other ways, we might just have to accept it. Right? Especially if it's a question of competing preferences, but not necessarily core values. Is it a problem that, you know, Chinese telecommunication networks, you know, our dominate the Southeast Asia, right? I mean, if they're not being used to spy in those populations and harm people, we probably shouldn't care.

Those are the types of things that we're going to need to think about, right? The world is going to change, we're going to need to change with it. We don't have to accept everything, but we're going to need to accept some things. I think the final thing that I would say, would be that US China competition that they will hear about our news does not have to turn into conflict, if we don't let it. We can seek areas for cooperation. We shouldn't demonize one another, we should seek to understand one another, and, and cooperate where we can and have reasonable disagreements where we can.

Emma Atkinson (17:25):

A big thanks to our guests, Korbel professor Suisheng Zhao and Collin Meisel from the Pardee Center, for sharing their expertise with us on this week’s episode. More information on their work is available in the show notes. If you enjoyed this episode, I encourage you to subscribe to the podcast on Apple Music or Spotify—and if you really liked it, leave us a review and rate our work. Joy Hamilton is our managing editor, and James Swearingen arranged our theme. I'm Emma Atkinson, and this is RadioEd.

By Francisco Rodríguez, Rice Family Professor of the Practice of International and Public Affairs

When a massive earthquake killed tens of thousands of people in Turkey and Syria in February, activists around the world scrambled to raise money for relief efforts through platforms such as GoFundMe. They immediately hit a roadblock: US sanctions. To comply with regulations, GoFundMe told users, it would not only block fundraising efforts mentioning Syria earthquake relief, but would suspend the accounts of those making requests.

Facing public outcry, the Biden administration issued a special, limited-time licence exempting Syria earthquake relief transactions, after which GoFundMe allowed the campaigns to go ahead. Yet while this carve-out may have eased some difficulties in bringing aid to victims, no such exceptions exist for other countries under US sanctions.

This article was published on May 4, 2023 in The Financial Times. To continue reading, please click here.

Korbel School Professor Keith Gehring speaks to a group of Ukrainian mayors.

The group of Ukrainian mayors who visited the University of Denver last week may not have been a typical delegation to the annual Cities Summit of the Americas, but their presence on DU’s campus was impactful, nonetheless.

The five mayors spoke with Korbel School of International Studies professors Rachel Epstein, Martin Rhoades and Lapo Salucci about their experiences leading their citizens through Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, a war which has displaced more than 14 million people. The roundtable included mayors Vitaliy Klychko of Kyiv, Ihor Terekhov of Kharkiv, Ivan Federov of Melitopol, Yuriy Bova of Trostyanets and Oleksandr Kodola of Nizhyn.

Despite the heavy human and infrastructural toll the war has taken on their cities, the mayors centered much of the discussion on the regrowth that has been achieved in the past few months.

Mayor Kodola of Nizhyn, a northern city in Ukraine’s Chernihiv region, spoke through a translator. He said the fighting in Nizhyn lasted a month and a half, resulting in many casualties and much destruction.

But he said he was proud of how the city has rebuilt following the conflict.

“For more than one year, we’ve given life back to our city and restored [it] to full capacity,” he said. “My task as the mayor is to restore life in the city.”

Bova is mayor of Trostyanets, which was occupied by Russia on Feb. 24, 2022, and liberated just over a month later.

He said that Russians tortured and robbed Trostyanets’ citizens, stealing all of the city’s computers.

“But almost 99% of people have returned to the city,” Bova said.

He thanked the U.S. for its role in supporting Ukraine through the war, saying, “[A] huge part of restoration of the city is due to international connections.”

Following the mayors’ conversation with professors Epstein, Rhoades and Salucci, the group attended a presentation by Korbel professor Keith Gehring that detailed several possible scenarios for Ukraine’s recovery, as determined by the Frederick S. Pardee Center for International Futures.

Gehring shared that the Pardee Center had developed four scenarios for Ukraine’s future pre-invasion by Russia—and said that the applicability of those predictions is limited but shouldn’t be entirely discounted.

Gehring then outlined four post-invasion scenarios: No war, war, success and misfortune.

The first scenario, “no war,” is counter factual, Gehring said.

“We do this so that we can baseline existing dynamics in the model and compare that with the alternative scenarios that are closer to our reality,” he said.

The other three scenarios are a closer representation of what is currently happening in Ukraine.

“We have to make bold assumptions, so the effects of war are resident in all three scenarios, but they also assume a stagnation or cessation in conflict by 2033,” Gehring said.

The “war” scenario includes approximated shocks to economic growth, trade, agriculture and the energy system and other potential shifts caused by Russia’s invasion.

The “success” scenario involves meeting top governmental targets for recovery in multiple categories, while the “misfortune” scenario sees recovery efforts fail to meet not only Ukrainian governmental goals, but also World Bank and European Commission targets.

Among Gehring’s key takeaways was a warning about Ukraine’s potential reliance on foreign aid—a factor that all the mayors expressed gratitude for during the roundtable discussion.

“In the near term, of course, aid will be essential. But that, too, is problematic,” he said. “[That] dependency [could] limit long-term growth as well the interests of the international community, which waxes and wanes.”

On April 4th, ICRS hosted peace activist and Code Pink founder Medea Benjamin. Listen here for a short conversation with ICRS Director, Aaron Schneider.

This article appears in the winter issue of University of Denver Magazine. Visit the magazine website for bonus content and to read this and other articles in their original format.

As China has grown its economy and international influence over the last half-century, it has become known as a major world power, working alongside—and sometimes against—the U.S. to advance its interests.

Now, new research from the University of Denver’s Frederick S. Pardee Center for International Futures suggests that China may overtake the U.S. as the world’s greatest power sometime in the next 20 years. If that happens, it will mean a very different world.

To get a handle on that different world—and possibly on how to avoid it—Pardee Center director Jonathan Moyer and his team use the International Futures (IF) model, developed at DU by professor Barry Hughes over a 40-year period, to forecast and examine development within major systems such as economics, demographics and governance.

“We’ve also done quite a bit of work on thinking about how to measure power and influence in the international system,” he says. “This is a really messy, kind of complicated area, because you can’t measure power and influence directly in an aggregate way, for a variety of reasons.”

But the IF model’s index-based approach allows researchers to measure these things—power and influence, specifically—in a more indirect way.

“We create indices that try to approximate measures of power and influence, and then we use those within the International Futures system to forecast what’s the most likely development trajectory,” Moyer explains. “Then, the last bit of the puzzle is to create alternative scenarios. So, we’re not interested in just simply predicting what’s going to happen, but instead, we’re interested in better understanding the range of uncertainty and the things that would have to happen to dramatically shift these development trajectories across time. That’s the focus of this kind of U.S.-China work.”

In most of the scenarios that the Pardee team played out—about 90%—China did overtake the U.S. as the world’s next great power. What would need to happen for the U.S. to remain in that top spot?

Collin Meisel, associate director of geopolitical analysis at the Pardeee Center, says that for the U.S. to remain the world’s No. 1 power, China’s gross domestic product (GDP) growth would have to slow—a lot.

“In the analysis that we did, we did look across a broad range of scenarios, and those included pessimistic growth forecasts for China,” he says. “But some analysts would say that we should be even more pessimistic. And so, if Chinese growth really stagnates, or if current GDP figures are sort of overstated, then there’s a chance that China wouldn’t pass the U.S. as the world’s leading power.”

Moyer says a world with China as the globe’s top power may look quite different than the reality we’re living today. For example, because China’s ambitions are disparate from those of the U.S., international conflicts could be managed in a different way.

“There are lots of other countries that have decent capabilities. The Europeans are still going to be powerful in the future; South Korea, Japan will still be influential in the future,” Moyer says. “And the world’s going to look very different with India. India’s going to be growing dramatically over the next number of years for the same kind of structural reasons. And so how does China deal with India [and Pakistan]—two-nuclear armed countries that have had border conflict?”

Diplomacy isn’t the only aspect of international dealings that could change under China as the world’s leading power. Moyer says the economic relationship between the U.S. and China might undergo some significant re-wiring—a strategic uncoupling of sorts.

“Let’s say you depend on someone for your daily lunch because they make a great sandwich, better than the sandwich you are able to make. If they become a jerk and start withholding that sandwich or raising the price of that sandwich, you’re likely going to make your own sandwich, even though it’s less desirable. Strategic decoupling is kind of like that—you stop depending on someone (or some country, in this case) for your well-being because you’re concerned about how that dependence can be used against you.”

The specifics of the situations aside, the researchers say that one thing is for sure: The countries that matter in the international system are changing, and tools and research can help us better understand how these changes will impact our lives.

The prolonged conflict in Yemen has created an urgent humanitarian and development crisis, resulting in hundreds of thousands of deaths, as well as significant damage to the country’s economy, physical infrastructure and education system. Now a new report details the devastating impact of the conflict and what is required to steer Yemen’s future in a positive direction.

The University of Denver’s Frederick S. Pardee Center of International Futures at the Josef Korbel School of Global and Public Affairs worked with the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) to research the human and economic cost of the war. Findings show the conflict is responsible for 377,000 deaths, a majority of which are indirectly attributed to the war due to diminished access to food, water and health care. If the conflict continues through 2030, the research indicates the death toll could climb to 1.3 million.

“Our research shows that the conflict’s full death toll is much higher than what is often reported, because the true cost of war includes deaths not just from fighting and airstrikes but from hunger and disease,” says Taylor Hanna, senior research associate at the Pardee Center. “But we hope that highlighting these grave findings will raise awareness of the situation in the country and the importance of bringing this conflict to an end.”

Research from the Pardee Center indicates that a Yemeni child under the age of 5 dies every nine minutes. A vast majority of the deaths are caused by hunger and disease. The county has lost $126 billion in potential gross domestic product since 2015. And 15.6 million people have been pushed into extreme poverty.

The Pardee Center uses system thinking and integrated modeling to map and understand the multiple ways that conflict affects development. Created by Barry Hughes, the International Futures (IFs) model is often used to predict the future of human and economic development worldwide.

“This series is the first time we applied long-term modeling techniques to better understand the effect of ongoing conflict on human development,” says Pardee Center director Jonathan Moyer. “This work highlights the applied research creativity and rigor of our team of researchers.”

Researchers modeled several different recovery scenarios, from a fragmented approach to an integrated recovery. According to the modeling, the former promises a difficult recovery, while the latter — which focuses on lasting peace, the economy, health and education, governance, agriculture and female empowerment — can return the country to its prewar development trajectory by 2030. It also prevents the deaths of 700,000 Yemenis and eliminates extreme poverty by mid-century.

“In what is considered the world’s worst and biggest humanitarian and development crises, a quick recovery can seem improbable," says Auke Lootsma, UNDP Yemen resident representative. "But the report demonstrates that within one generation, and with lasting peace, a brighter future for Yemenis is entirely possible. With the right policies, support and commitment of the international community, UNDP firmly believes that Yemen can rebuild itself into a prosperous, inclusive, and just nation for all.”

This report is the third in a trilogy of reports commissioned by the UNDP to assess the impact of war on development in Yemen. The first report, released in April 2019, revealed that the war had set back development by more than two decades and led to more death from indirect causes rather than conflict-related violence. The second report, released in September 2019, concluded that Yemen had the second greatest income inequality of any country in the world and second poorest imbalance in gender development. The third report explores post-conflict recovery and its impact on development in Yemen.

See here for fifteen takeaways from new report by the Pardee Institute and the Atlantic Council measuring US and Chinese global influence. Full report may be accessed here.

The Pardee Institute facilitated another in a series of International Futures (IFs) training sessions for more than 80 UNDP personnel from around the world on May 25, 2021. Pardee Center Research Associate Taylor Hanna presented the design and selected results of the Center's COVID-19 and Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) work for UNDP and Pardee Institute Director Jonathan Moyer demonstrated how IFs might be used further in this analysis.

Copyright ©2026 University of Denver | All rights reserved | The University of Denver is an equal opportunity institution