Do the Olympic Games Actually Promote Peace?

A University of Denver expert shares his take on international politics and sports during the 2024 Paris Games.

The Olympic Games symbolize many things: strength, togetherness, peace. But does the worldwide spectacle actually promote global harmony?

If you were to ask Tim Sisk, University of Denver professor of international and comparative politics, he would say, simply, “No.”

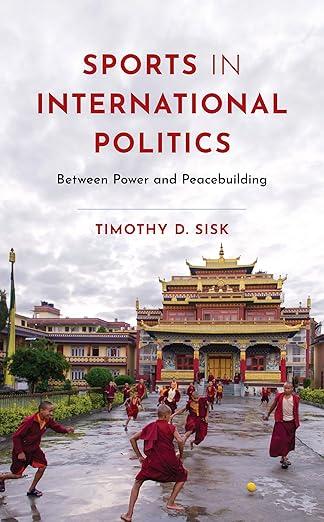

In his new book, “Sports in International Politics: Between Power and Peacebuilding,” Sisk argues that while the Olympics are often assumed to foster goodwill between nations at war, the Games don’t do much for peace.

“The Paris Games will come and go, and the world will still have conflicts in Yemen, in Libya, in Gaza, in Ukraine; and the Olympics will have little to no effect on those conflicts, to be sure,” he says.

Sisk, a 40-year scholar of international peace and security—and a lifelong sports fan—says that the Olympics have always reflected the patterns of history, rather than shaping them. He cites the Games’ hiatus during the First and Second World Wars and the political statements made during the 1936 Berlin Games as examples of how the Olympics is always “swimming in the currents of history.”

The intersection of the Olympics and international relations

Sisk asserts that every Olympics is affected by global politics in three ways.

First, he says, the Games embody, rather than influence, the politics of the day. Sisk says that this summer’s Paris Games, for example, are marked by the geopolitical rivalry between the United States and Russia, noting the International Olympic Committee’s (IOC) move to invite Russian athletes to compete solely as “individual neutral athletes.”

Second, Sisk asserts that the Olympics lays bare the inner workings of each host country’s political landscape. “It's been kind of interesting, as an outsider, to watch the Paris 2024 Games and how it relates to some of the internal tensions of France—to see that Paris Mayor Anne Hidalgo swam in the River Seine,” he says.

Sisk is referring to Hidalgo’s swimming stunt in the famously dirty river, which was put on to prove to the city—and the world—that the Seine is clean enough to host Olympic watersports competitors.

Third, Sisk says, are the ways in which athletes themselves use the Games as a stage on which to make political and social statements. In 1968, Black American athletes Tommie Smith and John Carlos, who respectively won gold and bronze medals in track, used their time on the medal podium to raise their fists in solidarity with the Black Power movement.

“What I think is interesting is that athletes often play this role in other countries of the world, too,” Sisk says. “So, when I look at the internal politics of South Africa or Iran, or even countries like Norway, the role of athletes—politically—is very important.”

“The world is a highly conflicted place at the moment,” he reflects. “There are 59 armed conflicts around the world—a record high since 1948.”

What to consider during this summer’s Games

Sisk says he’ll be thinking about three key issues as this year’s Olympic and Paralympic Games ramp up.

Paris 2024 will demonstrate the complete divorce between the IOC and Russia.

Just 15 Russian athletes are slated to attend this summer’s Paris Games.

“What we're going to have in Paris is only a very small handful of Russian athletes, and Russia is seeking to put on its own alternative to the Olympics, which they're going to call the Friendship Games,” Sisk says. “I personally don't see a way out of this for the International Olympic Committee, as long as the tanks roll and atrocities continue in Ukraine.”

Afghanistan will send a gender-balanced team to Paris.

In June, the IOC announced it would accept a six-person Olympic delegation from Afghanistan, made up of three men and three women, despite the Taliban’s ban on women in sports.

“There are a number of other Afghan women participating on the Olympic Refugee Team, including some talented cyclists,” Sisk notes. “So, if you're looking for some inspiration, follow the Afghan women's participation.”

Organizers of the 2028 Games in Los Angeles have the opportunity to do something big.

“I would love for the organizing committee of the 2028 Olympic Games in Los Angeles to consider rearranging the sequencing of the Olympics and Paralympics, and to put the Paralympics first,” Sisk says. “The Paralympics represent human resilience and innovation and ingenuity and courage, and having them come after the quote, ‘able,’ Olympics [means] we have our priorities wrong.”